Again and Again Tom Bills Sculptor

T om Croft ordinarily paints with the radio on. Merely when coronavirus swept through the U.k. this bound, the fifty-year-old artist from Oxford found he couldn't paint any more. "I was listening to rolling news, of things getting bleaker and bleaker, and I just ground to a halt," he says.

A take chances encounter with a doctor friend in Apr made him acutely aware of the pressures healthcare workers were under. "I asked him how he was doing, and he was besides tired to respond. He said, 'You don't want to know.'"

Croft asked himself what he could practise. "Pushing pigment around a canvass doesn't help a pandemic get abroad." But he started to think about the portraits of the great and the good that line our art galleries, and the fact that the Covid-19 pandemic will be one of the defining events of the 21st century. Why not commemorate NHS workers in the same way?

Croft posted on social media, offering to paint a free portrait of an NHS worker. Overwhelmed by the response, he widened the field, and over the following months matched more than 500 artists with doctors, nurses, paramedics and other frontline workers. "Anybody feels that NHS workers are undervalued," he explains. "We all know they should be paid more than. I idea this could be a way to raise their condition, a way of saying thank you. A portrait is a concrete thing – it exists in the real world, and will outlast united states of america all." Here are some of those paintings, and the stories behind them.

Nightshift: Nancy Faulkner, past Gillian Horn

Faulkner, 48, is a senior sister at the Royal London infirmary

This was painted when I had just been redeployed to the intensive care unit of measurement (ITU). I normally work in the ear, nose and pharynx department, merely I take a background in trauma and intensive care, so I knew early on that I wanted to be somewhere I could exist useful. Yous can meet the exhaustion on my face up.

Information technology was like nothing I've ever experienced earlier, and I've seen lots of horrific things. The night shifts were the most challenging. We had six patients in a ward that would normally have four. Yous'd be trying to care for patients who had just arrived, and others would be dying. And you lot're doing all of that in PPE, which is and so hot and claustrophobic. You lot'd desire to rip it off at the end of a shift, just you couldn't, because it was contaminated and dangerous.

I worked in the ITU for 12 weeks straight. We'd do ii day shifts and two nights shifts in a row, with two days off in between, which were spent sleeping. I've never known exhaustion similar information technology: if I saturday down for v minutes I'd fall asleep.

I was diagnosed with PTSD this summer. Information technology's been actually difficult. When Gillian delivered the painting to me, I'd been off work for a few weeks with severe symptoms. It was emotional seeing the painting, but also healing. It made me realise that I am out of the situation, and safe over again. And information technology helped me to acknowledge what I had been through.

Horn, 52, is an artist and architect, from London

I institute painting Nancy incredibly moving. I'd never met her, merely felt connected to her afterward so many hours poring over her face, and studying her Instagram posts. I wanted my painting to capture the weight of Nancy's experiences: a sense of the physical and emotional toll, merely as well her compassion and resilience: her humanity.

Trauma, by Alastair Faulkner

Peter Davies, 32, is an orthopaedic surgeon and trauma registrar at Ninewells infirmary, Dundee

It was weird, going to work in the early weeks. I'd be driving in and mine would be the but auto on the road. At the hospital, you think nigh Covid-19 all the time. Then you lot come out of hospital, and every time you plow on the Idiot box or look at a paper, information technology's there. It's constant.

I wasn't redeployed, then I carried on my usual work as an orthopaedic surgeon. People sometimes forget that the residual of the hospital doesn't but end: people still break basic, and demand surgery. Having to wear full PPE in theatre was tough. It's extremely sweaty, and hard to communicate.

I haven't been able to see my parents since Feb. Fifty-fifty with the best precautions in the world, it's almost impossible to avoid existence exposed to the virus in the hospital, and I couldn't live with myself if I gave them Covid-19.Zoom has made things easier, but it'south a long time.

Faulkner, 32, is a surgeon and artist based in Dundee

Every morning we talk over any new patients who accept been admitted: information technology'due south known as the "trauma coming together". I wanted to paint a group portrait showcasing all the different squad members involved and delivering patient intendance. I took inspiration from Renaissance painters including Da Vinci and Caravaggio, every bit well as historical paintings depicting healthcare workers, such as Rembrandt's Anatomy Lesson Of Dr Nicolaes Tulp. I wanted to paint something in that style, but juxtaposed with modernistic subjects and context.

The painting encompasses ii huge factors in my life: my love of surgery, and art, which is why I painted myself into the group portrait. Working on the painting during the pandemic really helped me mentally and kept me focused. I hope it represents everything good most the NHS I piece of work in, and love.

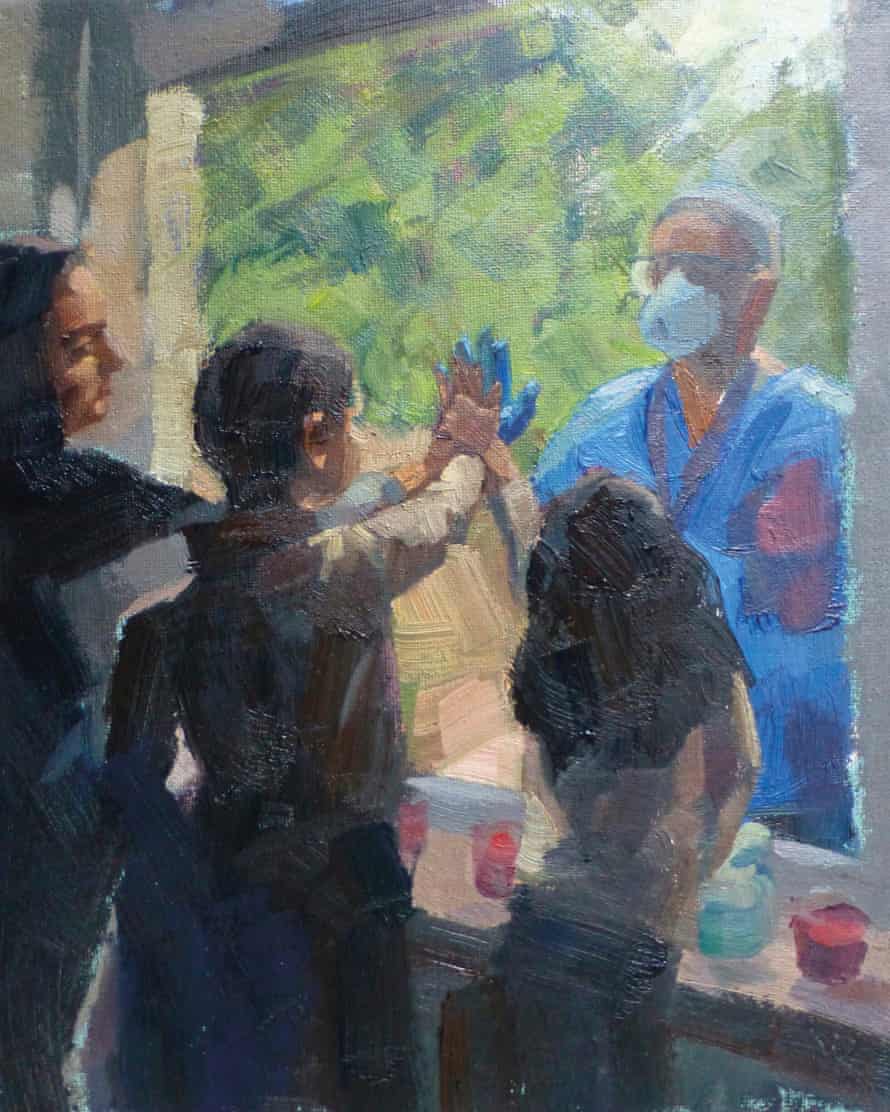

Dr Salman Visiting His Family unit, past Nick Richards

Dr Muhamm advertising Salman, 36, is a gastroenterology registrar at James Melt university hospital, Middlesbrough. During the outset wave , he was redeployed to the Covid-19 ward.

I spent half-dozen weeks living abroad from the family home – from my married woman and three children, who are five, seven, and nine, because 1 of my daughters is asthmatic. This painting is based on one of my rare trips to encounter my family unit, through a window.

When doctors and nurses started falling ill and dying with Covid-19, I had to explain to my kids that Dad might not be coming habitation. My youngest daughter said, "Where are you going? I'll come up with you lot." But my oldest understood that meant that her dad might die. I think she was quite traumatised past that. Nosotros lost a few nurses to Covid in my trust, and a doctor. A lot of my colleagues have long Covid, with lifelong irreversible impairment to their fretfulness.

The fact that we have one of the highest bloodshed rates in the world is bloodcurdling. I don't think the authorities has handled this well. We had enough time to prepare ourselves; we should have looked at Italian republic, and got ready.

The cases are starting to ascension once more in my infirmary. A lot of people are going to lose loved ones in the adjacent few months. I am dreading having to play God: deciding which of my patients I'm most likely to exist able to relieve. Making decisions like that never leaves you.

Richards, 49, is an artist from Sydenham, London

I found Dr Salman through Facebook. The image he suggested – being separated from his daughters through the drinking glass – was very powerful. I wanted to avoid sentimentality, and then I used a assuming, impasto technique, with thick oil paint and a large castor. It was about conveying raw emotion in an expressive way, rather than focusing too narrowly on detail.

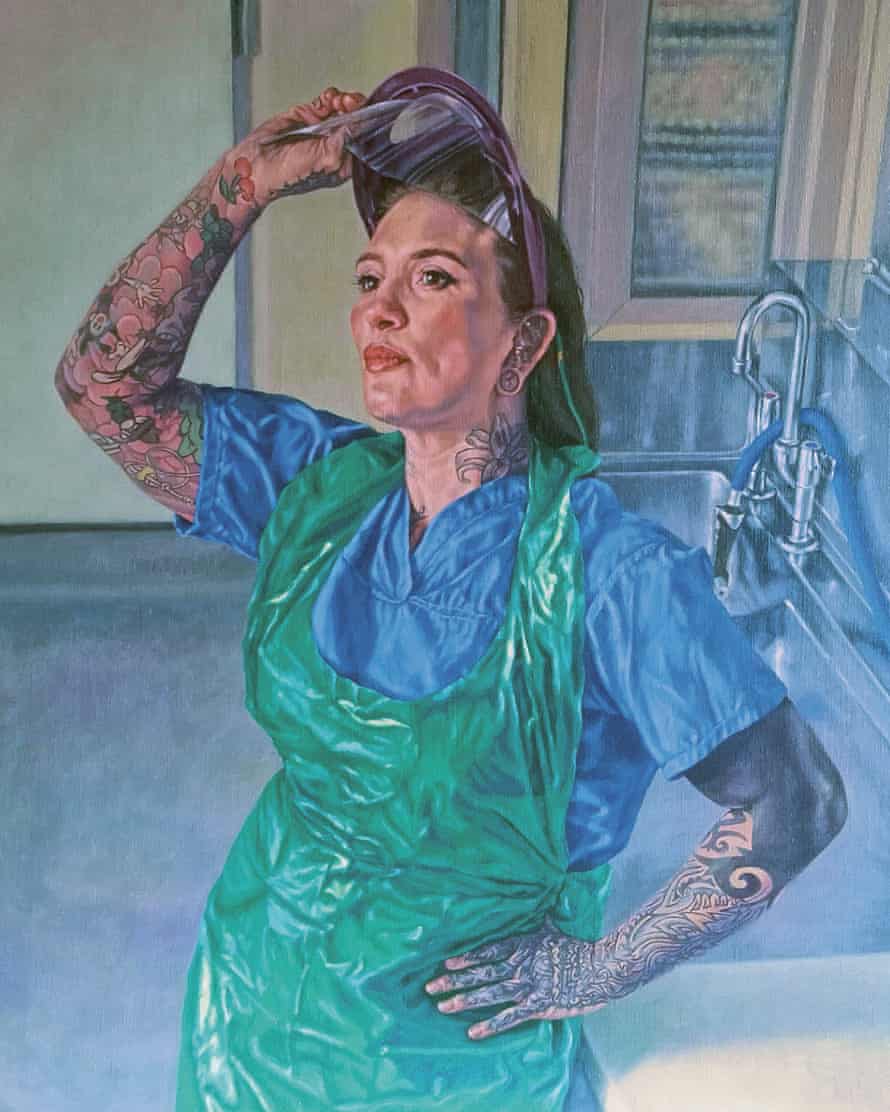

Katie Tomkins, by Roxana Halls

Tomkins, forty, is a mortuary and mail service mortem services manager at West Hertfordshire hospitals NHS trust

I've been doing this for 21 years; I worked in the aftermath of 7/7 – but this was something different.

Nosotros had our offset Covid death in March, and within a fortnight it was similar a storm had descended. We were running out of infinite. People were dying faster than nosotros could move them through. In addition, I was worried nearly my staff falling sick. How would nosotros manage if they had to cocky-isolate?

Nether normal circumstances, a big function of my job is liaising with families and guiding them through the process of viewing their loved ones. Information technology was hard to not be able to do that. Having to tell bereaved families over the phone that they couldn't say goodbye was tough.

When I look at Roxana's painting, I see someone who's exhausted, slightly burned out, but determined to get the task done. That'south exactly how I felt.

Halls, 46, is an artist from London

When I met Katie via video link I was awestruck by her force and tenderness, but also past her distinctive appearance. She reminded me of the wartime portraits by Dame Laura Knight, and the famous image of Rosie the Riveter from second world war posters. I wanted my portrait to evoke that same sense of focus, resolve and heroism. Having the opportunity to paint someone as remarkable as Katie, and illuminate the critical office of mortuary care, has been an accented gift.

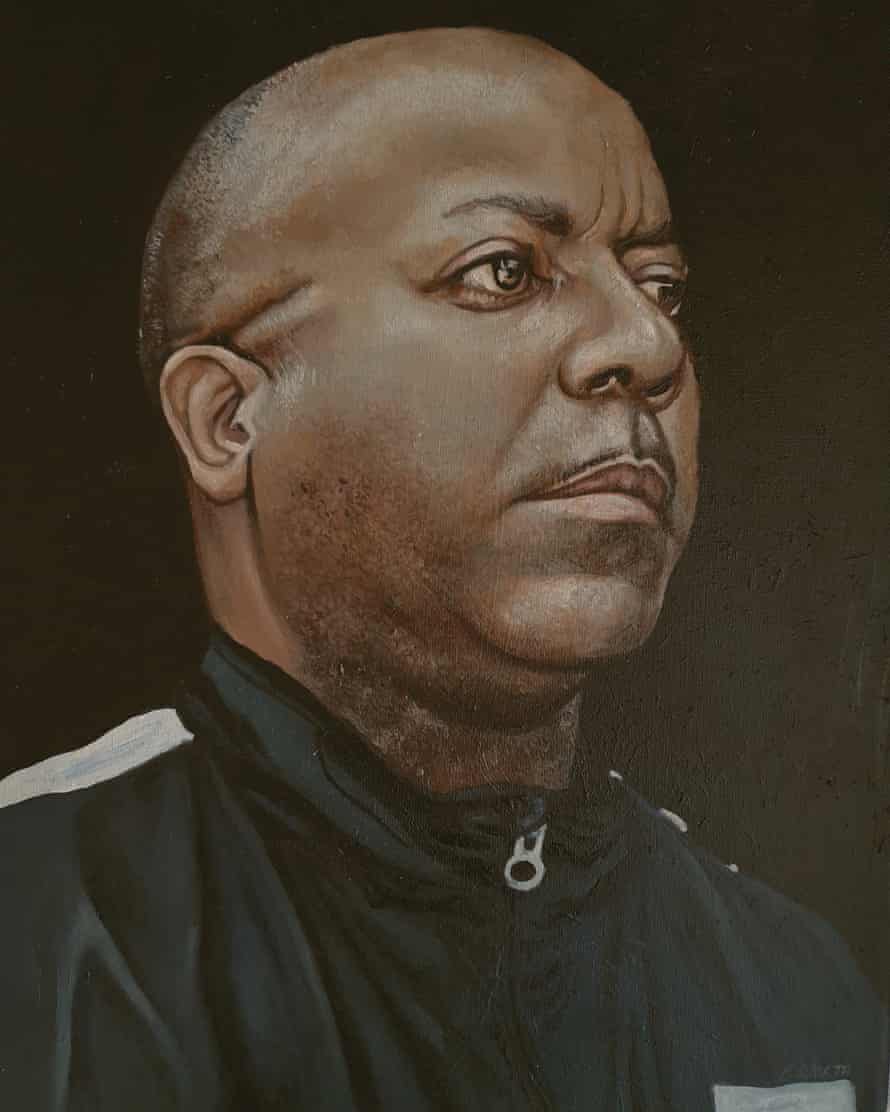

Jermaine, by Emma Worth

Jermaine Wright was a senior pharmacy technician at Hammersmith hospital, London. He died of Covid-19 on 27 April , at the age of 45. His friend and colleague, Alison Oliver, 46, a senior lead chemist's technician, remembers him

Jermaine and I went to school together. And then, years later, he came for a job interview in my department. I couldn't believe it. It was strange at first, because I was his boss, simply we became practiced friends.

Jermaine would always tease me. He'd tell people I used to be really bad at school, when I wasn't! He was exactly the aforementioned as he was at school: popular, cheeky. Every Valentine's Twenty-four hours, he'd bring in chocolates for everyone. He was a difficult worker: he'd e'er exist the first person in and the last out.

The solar day we establish out he had died was horrific. My boss called a meeting and the minute she walked into the room, I could tell from her body language that Jermaine was dead. I couldn't stay in the room.

There are but 10 people in my team, and Jermaine'southward loss has affected u.s.a. hugely. I cried for weeks. We speak about him all the time. I feel it's important to bring upward his proper name, and then he's non forgotten.

We screened Jermaine'due south funeral on Idiot box at piece of work, and more than than fourscore people turned up. That shows how loved he was.

Worth, 34, is an artist from Liverpool

I felt such a sense of loss and responsibility every time I picked up my brush. Jermaine'due south friends described him as the life and soul of the party, and so I wanted to reflect that energy. I feel very grateful to be able to tell his story: how brave he was, and what a hero.

Liam Halliwell, by Laura Quinn Harris

Halliwell, 41, is a paramedic for the North West ambulance service, based in Manchester

I've never experienced anxiety at work before, but those first few weeks just before lockdown, there was tension in the air. That's my overriding retentivity: the anxiety.

In my job, I spend time in the control room, triaging calls. I call back getting a telephone call from a physician: information technology was startling how unwell she was. She was struggling to speak on the phone. She was only in her late 30s.

One of the hardest things almost my job is that you accept this intense, cursory period of time with someone, where you lot're doing everything you tin to help them, and and then they get to hospital, and that's the last y'all come across of them. Y'all wonder how they got on.

The call rate in the early weeks was relentless, just then people got scared of going to infirmary, so they stopped calling so much. I got sick with Covid-19 in April. That was scary, because my son has asthma. I was terrified I'd pass information technology on to him. Thankfully, I recovered OK – and he was fine, also.

Quinn Harris, 36, is an creative person from Wigan

Liam is a friend; I wanted to paint him equally a token of my gratitude to him, and all the other key workers. I promise his kindness and dedication shine through.

Ma Soeur, past Donna Maria Kelly

Nikki Hedges, 33, pictured with her sister Becky Sheppard, is an organ donation specialist nurse at Luton and Dunstable university hospital in Bedfordshire

When I was 18, I went to South Africa for two months, and seeing the poverty there made me realise how much I'd taken the NHS for granted. That was what inspired me to railroad train as a nurse. My sister Becky works in the aforementioned hospital as me, although in a different department, and having her there during the pandemic was such an emotional back up.

The photograph that Donna based her painting on was one I took on a break in my shift to send to my family. Information technology was simply meant to exist a quick selfie, but it really captures the bond that Becky and I take.

So many people died on their ain. It was horrible having to plough away people who wanted to say goodbye to their loved ones. I nursed a onetime colleague; she was intubated and unconscious, so she won't think it. It was such a horrible shock, seeing her come in. We didn't retrieve she was going to make it, only she did. Watching her recover was special.

The aftermath has been really hard. I've been off work with PTSD, and I am seeing a psychologist. You can feel actually alone. But I want people to know that NHS staff are human also. There's no shame in reaching out for help.

Kelly, 42, is an artist from Hertfordshire

When Nikki contacted me to enquire if I could pigment a portrait of her with Becky, I said yes immediately. I was separated from my own family for the offset few months, and have two sisters, then I know how special that bond is. I wanted to bear witness the love that was conspicuously at that place, only also express my respect for the NHS. It saved my girl's life 8 years ago, when she was hospitalised with a heart disease. I am thankful every twenty-four hour period.

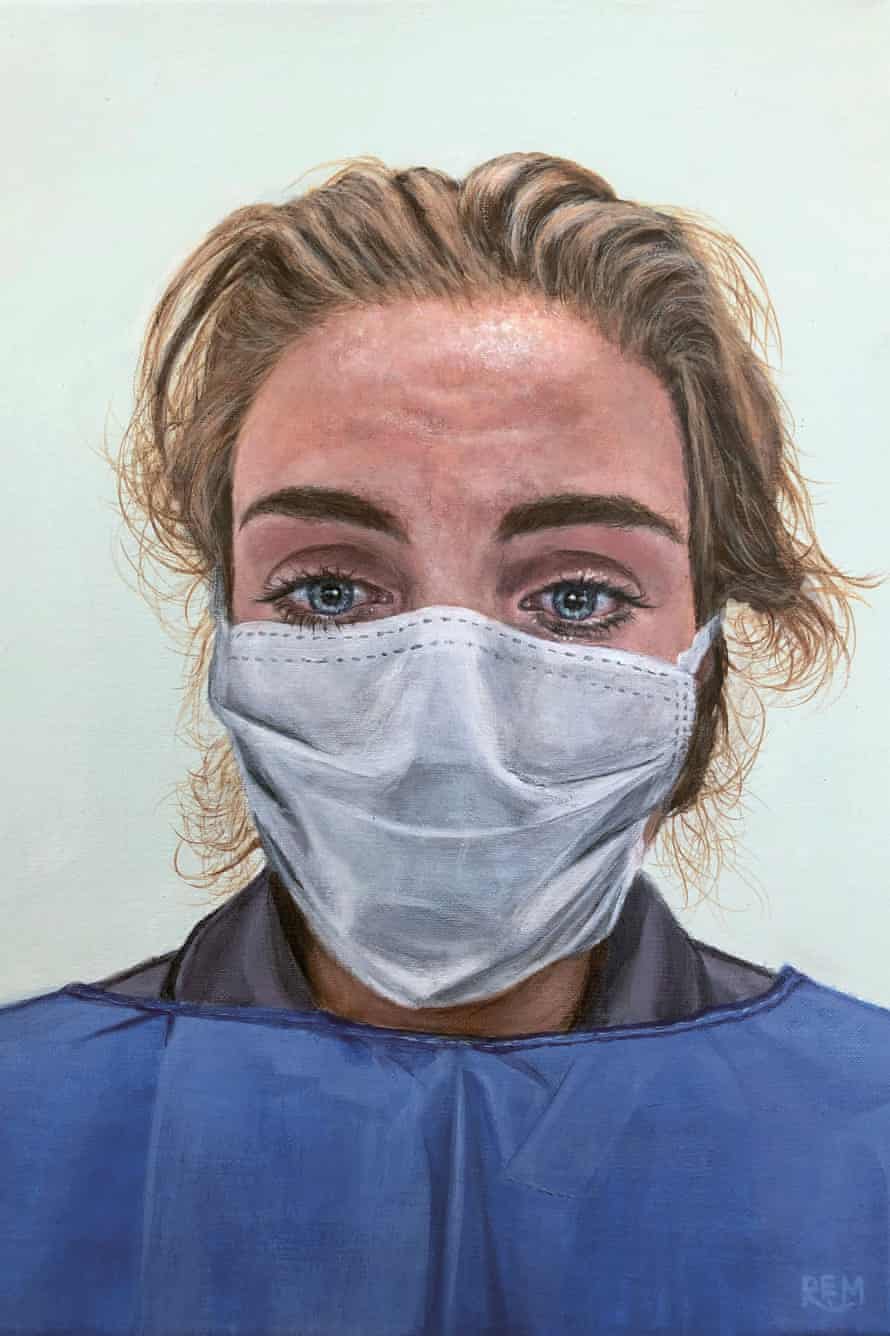

1000000, past Rosie Mark

Megan Cavanagh, 26, is a newly qualified nurse at Aintree university hospital near Liverpool. During the pandemic, she volunteered as a student nurse

It was my task to sit down with people as they were dying from Covid-19, and comfort them, hold their hand. At that time, we weren't allowed visitors, so information technology was just me with the patients as they drew their terminal breaths. You'd exist trying to be strong, and non bear witness any emotion. Sometimes they'd say that they wanted to see their family. I merely held their hand and told them that everything would exist OK. In that location was nothing else I could say. At night, I'd go abode and cry.

Since the first moving ridge, I've qualified and moved to a different ward. Terminal calendar month we went into lockdown again. My ward has dementia patients, and around half have Covid-19 now. I'k five months meaning, and then I'm working in the role considering I'm loftier risk. But the staff are under a lot of pressure, specially because dementia patients tin can get unsettled. I'm praying that when I come up back from maternity exit, this pandemic will be a distant memory.

I have set a memory box, with the portrait Rosie painted in it, and thank-you cards from the families of the people I helped. For the rest of my life, I will be proud of myself for working through the pandemic, and especially for beingness with those patients in their final hours.

Mark, 58, is an creative person from Crossford, Scotland

The photo this was based on had been taken at the stop of a long and hard shift, and Megan was drained. I wanted to convey the physical and emotional toll the pandemic was taking; I think information technology can be seen in her optics.

NHS Hero – Dr Sekina Bakare – Intensivist, by Emma Woollard

Dr Bakare, 36, is an ICU and anaesthetics doc at Charing Cantankerous hospital, London. During the showtime wave , she was based at Northwick Park hospital, London

Emma managed to capture the defiance of our fight. My expression communicates not only the struggle that all healthcare workers were going through, but also a sense of power and calm. She portrayed a strong Black woman in medicine.

That confidence came from being in a supportive environs. Northwick Park was desperately striking, but there was such a sense that the community was rallying around u.s.. People brought food into the hospital, sent us cards. Schools donated PPE. I saw the all-time of our country then: compassion, generosity and unity. Existence abroad from my 2 immature sons was tough, but it was astonishing to be able to come abode and run into them in the evening.

I'm Blackness British, of Nigerian descent. It was scary seeing a lot of people coming into infirmary who were seriously unwell, and who looked like me. It was besides actually hard when colleagues fell sick: quite a few health workers ended upwardly in intensive care. I remember when one nurse was discharged from hospital: nosotros lined the corridors to applaud her out. That moved me to tears. Not all of my colleagues fabricated it.

Woollard is an creative person from Notting Hill, London

Afterwards a video call with Sekina, I had a strong thought of how I wanted the portrait to look. Sekina is non but very cute but projects this powerful sense of calm. I asked her to get a colleague to photograph her in profile. I wanted to portray Sekina's force, focus, and tranquillity, amid the chaos.

I spent six months in an NHS infirmary past my female parent'southward side as she was dying, and information technology gave me an idea of how heroic the staff are. It can be easy to accept the NHS for granted, until yous travel to other countries that don't have universal healthcare – and realise how lucky we are.

Dr Oge Igwe, by Heidi Hart

Igwe, 32, is a doctor working at Furness general hospital, Barrow

I worked in the Covid-19 ward for six months, during the superlative of the pandemic. You felt such an extreme range of emotions: satisfaction when yous saw that people were getting better, and frustration when the medical interventions weren't working.

This projection felt like the best of humanity coming together. You had people similar Heidi, who are then talented, giving their fourth dimension, and other people like my colleagues, working together for the good of everyone on the ward. When I saw the painting I was very pleased with the level of artistry that went into it. You could tell how much love she put into it. If someone saw that on the wall of my house, they'd think I paid a lot of money for it.

I moved to the U.k. three years ago, from Nigeria. I think British people don't always realise this, because they're used to it, merely the NHS actually is the best gift that British people accept.

Hart, 47, is an creative person from Hilperton, Wiltshire

It was difficult to notice time to chat with Dr Igwe, because he worked such long hours. And then I went through his Instagram folio instead, and found the perfect image to base of operations my portrait on. He'south slumped over, wearing his uniform, looking tired and wrung out. Information technology actually summarised what all the frontline staff were going through. Nothing any of us could do goes far enough to thank the NHS staff for what they've washed this year, simply I hope that Dr Igwe feels a bit more appreciated, with my painting.

-

Portraits for NHS Heroes initiated by Tom Croft is published by Bloomsbury Caravel on 12 November at £25.

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/nov/07/seeing-the-painting-helped-me-heal-nhs-workers-on-canvas-tom-croft

0 Response to "Again and Again Tom Bills Sculptor"

Post a Comment